Episode 2: Melody Follows Harmony

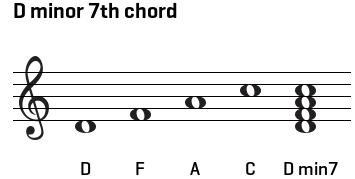

So how do these musicians improvise melodies that “go”—or sound right—with the chord symbols—or harmonies—of a song? Well, remember that a chord symbol stands in for a cluster of notes. As we explained earlier, a d-minor-7th chord consists of four notes.

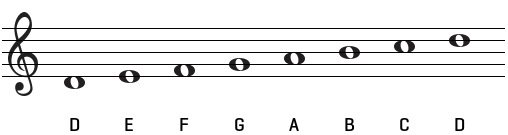

If you’re improvising on that chord, those four notes are obviously important. But that chord also suggests a whole scale of notes that are appropriate and would “fit” with the harmony. Technically this isn’t a “d-minor scale,” but it is the scale suggested by a d-minor-7th chord when it is part of a “chord progression." More on that later.

A Possible Scale for a D minor 7th chord

An improvised solo would be pretty dull if the musician just played an appropriate scale for every chord in a song’s changes. That’s where the creative talent of a jazz musician comes in. These notes are simply the basic, raw material of a solo, and how a musician uses them is what gives each jazz improviser his or her signature sound or style. Some solos will stick close to these basic elements, and some will push the boundaries, expanding harmonies or creating dissonance and tension. Some solos are fast and muscular, cascading through scales with intense energy. Others are lyrical and elegant, creating melodies and motifs that could stand as a song in themselves. We’ll look at the different styles of soloing when we talk about pioneering individual players who are remembered for their distinctive way of building a solo.

The Tension and Release of Chord Progressions.

If you’ve ever taken a music class in school, you might have heard about harmonic tension and resolution. A lot of music—in all genres—is built on that idea. Most music has a “center” to it, and a piece of music is generally a journey that starts at that center, moves away from it in interesting ways, and eventually goes back to that center. In a classical symphony or sonata, you can usually hear the “center” in the last few moments of the final movement. It might sound something like this (it’s the finale to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.

The reason that finale sounds so…well…final is because it is hammering on the “tonic” chord—the harmonic home base of the piece. Generally speaking, the music preceding that finale has been moving toward that home base, but taking a path that is more like a mountainous ramble than an as-the-crow-flies straight shot.

Putting it another way, that “finale chord” is the final resolution of a whole series of harmonic resolutions. Most music we listen to today—on the level of melody and harmony—is about creating tension and releasing it. Think of the famous build up in that Phantom of the Opera organ solo (otherwise known as Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor).

That big, echoey chord builds and builds until you practically can’t stand it! And then it “resolves.” Ahhhh. Tension and release.

That buildup is an extremely dramatic example of the way music moves through time, creating suspense of a sort, in the same way a film director, playwright or novelist plays with your emotions in a suspenseful scene.

That idea—tension and release—is a key principle to move music through a composition, whether it’s a song or a symphony. We may not sense it as a tense buildup and a satisfying “ahhhh,” but in subtle ways, music plays on our natural inclination toward “resolution.” Our ears want some harmonic chords to move in a certain direction. They also want a the music to move toward a home base, like those thundering final notes in the Beethoven symphony. Songwriters use that natural desire to move music along. And they can have fun with it, leading your ear toward a satisfying resolution, then changing directions in a surprising ways (music folks call these “false cadences”).

These sections of tension and resolution can divide songs into neat, symmetrical segments. In songs in the AABA form, the “B” section often starts in a different—sometimes surprising—key. Musicians can use those structures as a template for improvising, building improvised phrases that move away from a “home key” and then toward it in the course of a four- or eight-bar section.

But a great jazz solos isn’t just about following the right chords and making up strings of notes that “fit.” Move on to the next section, and we’ll talk about the true artistry of improvisation.