Episode 1: The Basics of Improvising

When I was in college, I was a huge fan of one of the great contemporary jazz pianists, Keith Jarrett. He’s had a long and storied career, but is particularly well known for his solo improvisations. Listen to this excerpt from one of his solo concerts, and you can hear why:

The Köln Concert was one of dozens of Jarrett’s recordings that capture his completely improvised performances. He would simply sit at his piano, gather himself, and play—“make up” 20 or 30 minutes of music on the spot.

I was fascinated with this, and spent a lot of time in the jazz rehearsal room trying to do something similar—in my own modest way. Occasionally, I’d play at the campus coffee house. After one of those nights, a friend came up to me and complimented me: “How do you memorize all those notes?!”

The short answer to that question, or course, is that the music isn’t memorized. I couldn’t sit down and repeat even a short excerpt of what I had just played if I tried.

But there is a lot to remember, and a lot to learn, to get to the place where you can play jazz well (I am still a enthusiastic beginner). And a first important step to appreciating jazz music is to understand what’s going on in a jazz musician’s head when they’re improvising.

Improvisation is the heart of jazz music. Individual players may have his or her own unique tone—the silky smooth tenor saxophone of Ben Webster, the brash trumpet of Freddie Hubbard—but it is their approach to improvisation that establishes their musical identity.

FOLLOW THE “CHANGES”

So what does it mean to improvise? As the word suggests, a lot of improvisation is making it up as you go along. But like “improv comedy,” any improviser works within a set of rules or guidelines. Members of an improv comedy group can build or riff on each other’s lines or bits, but a group can’t function unless each member stays within some agreed on boundaries. The same is true in a jazz ensemble. Each musician works within an agreed on musical structure. As in almost all music, that “structure” is determined by melody, rhythm and harmony.

If you are playing or singing in a group, you all have to follow the same beat, of course. Sing “Happy Birthday” with a group of friends, and you all hit the same notes at (approximately) the same time—that’s the melody and the rhythm.

But perhaps some your musically adventurous friends might “harmonize” the final few notes. It’s not hard to do if you have a good sense of pitch, and many people can do it by instinct. If you have ever tried to harmonize, you know that some harmony notes “fit” and some don’t. If a note fits, it’s part of the harmony that goes along with the song’s melody.

If you sing in a chorus, you know that the music is arranged into parts that create chords—harmony—along with the melody. When a guitarist strums behind a folk singer, the chords he plays create harmonies behind the melody of the song. Even when an instrumentalist plays a simple string of single notes, there is usually an implied harmony behind the melody—an architecture supporting the notes.

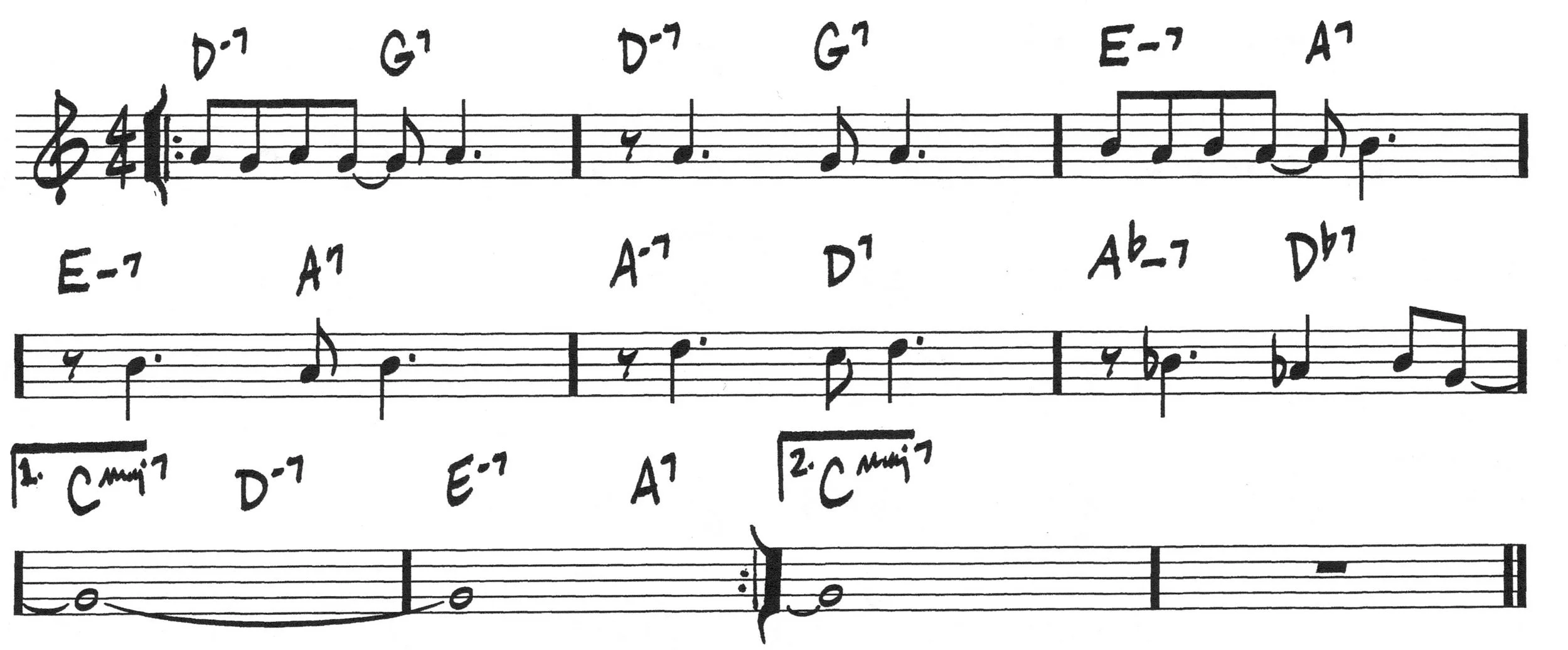

When a jazz musician plays a solo, she is working within that architecture, creating melodies that relate to the harmonies of a tune. (Jazz musicians call them “changes,” short for chord changes.) Remember the “chart” for Duke Ellington’s “Satin Doll”?

The notes on the staff refer to the melody of the song. And the letters and numbers above the staff refer to the harmonies. The harmonies are what a soloist “works with” when she is improvising. There are four beats to a measure here (4/4 time), so the harmonies of the song change every two beats: “D minor-7,” then “G-7,” then “D minor-7”, etc.

When a jazz musician plays a solo, she is working within that architecture, creating melodies that “fit” the harmonies. In the first two measures of “Satin Doll,” the two chords—“Dm7” and “G7”—suggest a particular set of notes. Basically, a musician improvising on those two measures would use those notes to create a new melody. It might be something simple and hummable, or it might be an explosive string of rapid-fire notes. That’s up to the improviser. And while those chords might be a starting point, an adventurous and experienced improviser might push against those harmonies in different ways. Or abandon them altogether and take the song (and the musicians playing with her) in a different direction altogether.

The clearest way to hear an improviser at work is to listen closely. Let’s hear another version of “Satin Doll,” this time by a quartet in which everyone takes a turn to solo. The leader here is trumpeter Clark Terry, who played with Duke Ellington’s band through much of the 1950s:

After the short piano intro, Terry plays the melody (or “the head”), and then each musician takes a solo, some of them traversing several repetitions of the song’s 32 measures (or “bars”). First, pianist Duke Jordan improvises through two repetitions of the song (1:19-3:12). Then Terry takes a turn (notice how the pianist stops playing—or “lays out”—during part of Terry’s solo, to allow him greater freedom to improvise because he can alter some of the harmonies without worrying about the piano following along).

After the trumpet solo, bassist Jimmy Woode takes a few choruses (5:19-7:44). The piano and drums drop the volume down to a whisper (or lay out entirely), allowing the low, low notes of the instrument to be heard. Woode really tears into the song, singing along with the notes as he plays them, making little musical “jokes” along the way, eventually shifting into a different rhythm—”double time”—and urging the drummer, Svend E. Norregaard, to follow suit. But even when Woode is out there on his own (with perhaps just a bit of cymbal to articulate the beat), he’s using the harmonies and structure of “Satin Doll” as a template. Try humming the melody of the song along with him, and you’ll hear that it all fits together.

Sometimes a drummer will play an extended solo, but it’s also common for the drums to “trade fours” with the other musicians: the group plays four measures of the song with one member taking a short solo, then the other musicians drop out and let the drummer solo for four measures. Here (7:44-8:23), Svend Norregaard does just that, taking a few solo breaks to show his stuff before Terry wraps the song up by playing the last section of the melody (8:23-9:05).

So what’s going through these musicians heads while they are improvising? Go on to the next section to find out more about how improvisation happens.