Episode 1: Reading a Jazz “Chart”

If you play an instrument—the piano, say—you most likely play from a sheet of music that looks like this:

This music (a Brahms Intermezzo) indicates the exact notes to be played—each “dot” corresponds to a single note, and the vertical lines indicate the rhythm of the notes.

Or perhaps your music looks something like this:

Not too different. But notice the letters and numbers along the top: C….C7….F….G7. Those letters indicate the harmonies (or chords) that go along with the melody. This is a simple piano arrangement (of Scott Joplin’s “The Entertainer”). There isn’t really a reason to pay attention to these chords. Playing the notes on the staff is all that’s expected. But an experienced pianist could use these symbols to “flesh out” the arrangement.

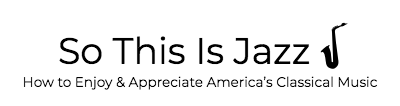

Now take a look at this piece of music:

Instead of a full, double staff of notes, this sheet music gives you only the harmony—indicated by the letters along the top of the staff—and the melody—the notes on the staff. This is the “road map” that an experienced jazz musician—no matter what instrument they are playing—will follow.

This is the first few lines of Duke Ellington’s “Satin Doll,” and here’s what it sounds like:

Pretty lame, huh?

That was me playing, and I followed the “road map,” playing the chords and melody that make up the basics of the song. A talented jazz musician, however, will use the basic elements of the song—this melody and its harmonies—to play it in her own, unique way. The chords and melody give her a very basic idea of the tune. But from those basics, a player can “interpret” a song in an almost infinite number of ways.

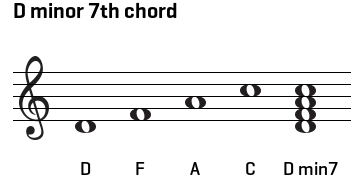

Take the chord symbols, for example. A “Dm7 chord” (“D-minor-seven”) suggests four specific pitches. Here’s what it looks like written on a music staff:

But a musician playing a piano or guitar can play those notes in dozens of different combinations, as long as they observe a few basic rules. The “D” is the “root” of the chord, so that almost always is at the bottom—the lowest pitch of the chord. But a piano or guitarists can get creative by playing the notes in different combinations, adding certain pitches, or even slightly altering some of the notes to add richness or color. So every pianist’s interpretation of the song is his or her own.

Here’s Duke Ellington himself playing a solo version of his song—in his own inimitable style:

The melody and harmony are just like the “straight” version you heard above, but Ellington adds so much more. He fleshes out the chords so they sound rich and sonorous; he subtly tweaks the rhythm to make it swing; and he adds little cascades of notes when there is a pause in the main melody—musicians call them “fills.” It’s now a song with lots of life and soul.

And after he plays the melody through the first time (musicians call this “the head”), he leaves the melody more-or-less behind and creates his own melody for a while. This is “improvising,” which we’ll talk about in a future episode (the improvised solo starts at 1:12). After the solo (at 1:56), he returns to play the first two bars of the melody before he ends the piece.

And just to show you how the same song can be interpreted in completely different ways, here’s Oscar Peterson performing with his trio (Ray Brown, bass; Ed Thigpen, drums):

Since Peterson is playing with a trio, he can approach the song differently. He lets Ray Brown, the bass player, play the fills between phrases of the melody. Like Ellington, he plays the head once through, and then launches into a solo (starting at 1:06). When he improvises, he can let the drummer and bass player maintain the steady beat while he can stretch out with long strings of notes and flashy chords. The improvised section lasts until 3:10, and then he ends the song by playing the first section of the melody.

So there you have it: two recordings of the same song, but the approach and style of each pianist are worlds apart. With “Satin Doll” as the foundation, these two artists craft distinct pieces of music. Jazz gives them the freedom to bring more of their own creativity into the process. In a sense, they are composing as they are performing. First by interpreting the song’s melody in a unique way, then by improvising on the song’s harmonies, creating melodies on the fly.

Creating those melodies—or improvisation—is the heart of jazz music. We’ll explore that more thoroughly down the road. But since we’ve been talking about Ellington’s “Satin Doll,” take a listen to this section’s Spotify play list, and hear how many different ways there are to play that jazz standard. Not sure what a jazz “standard” is? Head to the next episode and learn about some of the common road maps used by musicians.